Over the years, I have resisted referring to myself or Sher as shamans. I preferred wise man/wise woman. Basically, I didn’t want to be lumped in or identified with all of the workshop neo-shamans who think shamanism is nothing more than journeying, probably based on illogical and noncritical thinking that journeying with the mind is a form of “trance,” which would indict, according to Mircea Eliade’s definition of Shamanism, that they were shamans. The problem: this implies subtly anyone can be a shaman, which makes it very attractive to the consumer. But why not call yourself a shaman for material gain and status as the average person will accept you at face value just as the majority of people will accept organized religion and their mouthpiece at face value without using their common sense—no research just acceptance.

In reality, it takes years and years of apprenticeship with an Indigenous “persons of power” to be considered a shaman. Traditionally, this is only after having been identified as a “chosen one” for training either by the current practicing shaman, the ancestors (through dreams), and/or a medical/soul crisis. With this set of criteria, you couldn’t get many people to qualify for a neo-shamanic workshop.

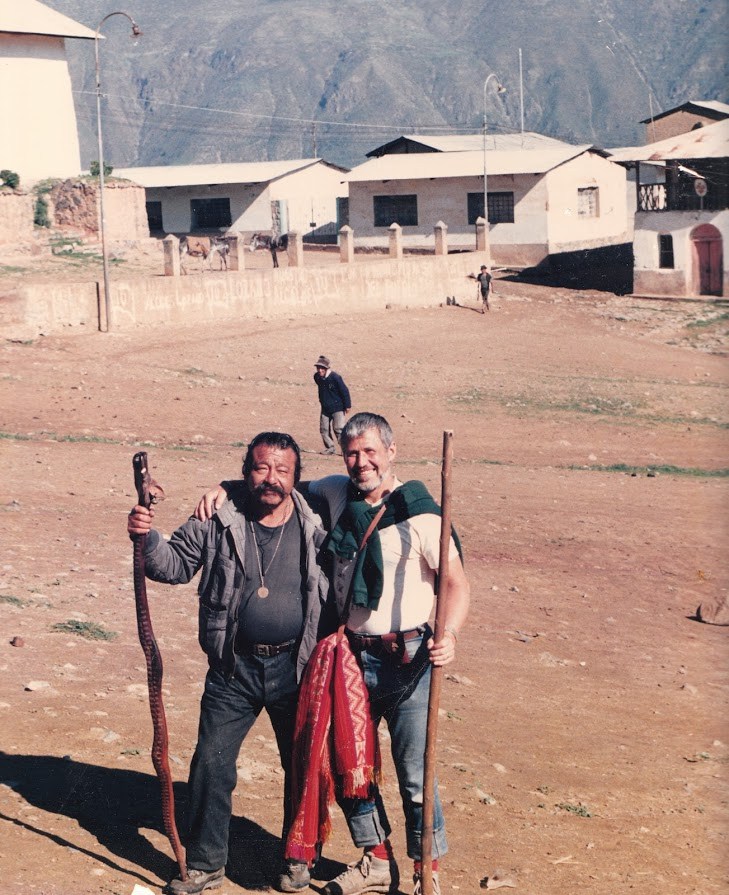

Even though my wife and I are holders of a Northwest Coast shamanic or medicine way’s lineage, I chose not to label myself as a shaman until recently as the identity and title needs to be changed to Earth Doctor. We are not seminar or workshop trained; our knowledge flows from our firsthand experience of it. We have not been observers but active participants, initiates, and carriers of shamanic lineages, ranging from my shamanic initiation in a sacred lagoon in the Andes after having walked the Inka Trail in 1988 (where I faced death, almost dying); to myself and Sher apprenticing with the late Coast Salish elders, Mom and Vince Stogan, who passed on to us, the right or license if you will, their Good Medicine lineage of bathing, burning, and healing. In line with the criteria above, Mom and Vince asked us if we would like to learn their “ways” only after having observed us doing our spiritual work. Moreover, we are Knowledge Carriers with our deeds of shamanic/medicine power having been witnessed and felt by others.

One last point: my descending spirit exorcism, Ko Rei, occurred in Japan in front of Kobo Daishi’s mausoleum at midnight on the sacred mountain Kōyasan in October of 1987. Kobo Daishi was the founder of Shingon esoteric Buddhism. The exorcism was conducted by Sakano-san, an esoteric or shamanic priest from Osaka who had a dream about me. He had come to the mountain to find me even though he had no formal connection with the temple where I was staying. This otherworldly kundalini experience, descending shakti, thrust me through a tear in the fabric of dualistic reality. It was the initial quickening of my awakening mind and resulted in a knowing of radical nondualistic interpenetrating reality.

With our decades of experience, it then makes sense we approach this subject of shamanism not solely from an archeological, scholarly, or New Age approach, but from our direct experience of the subject matter.

The Initial Problem Stems from Mircea Eliade’s Definition of Shamanism

The origination and meaning of the word shaman is not as straightforward as many are led to believe. With a lack of knowledge, insight, and experience, the meaning of the term has been co-opted to mean nothing more than going on journeys, so-called “trance work.” This was the foundation for the workshops of the late M. Harner, who propagated core-shamanism (his name for neo-shamanism). Done for profit and power, the power is illusory, profit is not, as Harner’s training to become a shaman doesn’t involve ascetic practice/training or years and years of study, experience (best in the outdoors in nature – experiencing mountains, waterfalls, streams/rivers and ocean) struggle, suffering, and fear. Workshops, and now hallucinogens, are all that is needed to call yourself a shaman. Not only is core-shamanism a problem but also Hawaiian shamanism or Huna. “Huna is not and never was Hawaiian. Huna in Hawaiian means something very small and insignificant such as a grain of sand.” And there are no accepted Hawaiian sources that refer to the word Huna as a tradition of esoteric learning. The native Hawaiians we have studied with, such as Auntie Margaret, say it was made-up by a white person and persons—haoles.

The problem should not, however, be understood to stem solely from the work of Eliade. The ambiguous, malleable nature of the word “shamanism,” which had become popular by the end of the 18th century, was lamented as far back as 1903 by the distinguished sociologist Arnold van Gennep, who described it as “a strange abuse of language.” Van Gennep complained, “We have inherited a certain number of very vague terms, which can be applied to anything, or even to nothing; some were created by travelers and then thoughtlessly adopted by the dilettantes of ethnopsychology, and used any which way. The most dangerous of these vague words is shamanism.”

Little progress has been made since van Gennep wrote. The word shaman “has come to mean many things to many people.” Eleanor Ott complained the term “shamanism” can be easily slipped on, in her words, “like a second-hand sweater, even when there may be no justification for it.” (An excellent example: neo-shamanism.) All of these writers imply that scholars often use the word mindlessly, either without bothering to define it or without subjecting their definition to critical thinking or examination.

Eliade was aware of the slippery nature of the concept of the shaman and, as we have seen, tried to produce a precise and workable definition of the concept. However, he clearly failed. For example, the notion of “trance,” which Eliade heralded as the definitive hallmark of shamanism, has come under scholarly attack for its imprecision. Eliade believed that trance was a form of ecstasy proper to shamans, who specifically employed it to confront the supernatural in the otherworld. The word “trance,” however, generally refers only to an altered, somnolent state (drowsy). As Roberte Hamayon, who studied Siberian shamanism, points out, “‘trance’ tells us nothing about what the shaman is actually doing” and cannot, in any case, be empirically verified.

We must also wonder how meaningful our Western notion of “trance” would be to Mixe shamans in southern Mexico, who reportedly do not differentiate between the dreaming and the waking. Indeed, Hamayon notes that “shamanistic societies do not make use of native terms homologous to ‘trance’” and “do not refer to a change of state to designate the shaman’s ritual action.” She concludes from this that “it even seems that the very notion of ‘trance’ is irrelevant for them. When asked whether the shaman is or is not ‘in trance,’ “They are for the most part unable to answer.” Moreover, some individuals considered by scholars to be shamans, such as the tan’gol in southwestern Korea, never enter a trance or experience ecstasy.

A New Perspective

According to scholars, the word shaman is from the Tungusic word šaman, meaning “one who knows. In Nahuatl (language of the Aztecs) philosophy, Tlamatinime, wise men – wise women are “they who know things.” Tlaiximatini, which means literally, ‘one who has firsthand knowledge [imatini] of the character or nature [ix] of things [tla]…’”

Some have suggested that the Sanskrit word śramaṇa, for Vedic or Buddhist ascetic, could be the ultimate origin of the Tungusic word since Buddhism did penetrate into the Tungusic regions in early times. This proposal has not found scholarly acceptance as the shaman is not an ascetic and his or her role is very different from that of the Buddhist priest. As a practitioner, teacher, healer, priest, and carrier of Indigenous shamanic traditions, I disagree. Due to my firsthand experiential knowledge, ascetic training is essential for shamanic powers such as healing/harming, foreknowledge, insights into the mysteries of heaven and earth, and becoming a šaman.

At this point, let me explain the pitfalls of using fragmented secondhand knowledge instead of direct firsthand knowledge based on life experience as a practitioner. Many scholars, but not all, approach their theories, premises and assumptions on information or knowledge that is secondhand and on their life experience as an observer. They are usually not active participants, such as Eliade, in the subject matter basing their writings solely on observation and the past writings of others, which are sometimes centuries old. Many times, these same scholars and researchers will introduce comparative philology and etymology into their scholarly thesis to justify and support their hypothesis. Once again this is without actual experiential knowledge of the subjects and the lands involved in their subject matter.

There are many problems with this secondhand approach when we are seeking truth. The word “shaman” only came to Europe in the late 17th century through the account of the Dutch traveler Nicolaes Witsen reporting on his journeys among the native people of Siberia in his 1692 book Noord en Oost Tatarye , which was based on secondhand knowledge.

I suggest we adopt both šaman and śramaṇa as the origination and meaning of the word shaman. On the other hand, we need to go one step further while still keeping the concept of šaman and śramaṇa. In addition to the word/term shaman, we also need to use what Vince Stogan preferred to be called: Indian Doctor or Medicine Man/Woman—shall we say, a doctor of the earth: a medicine man – a medicine woman, a practitioner of the “Medicine of Mother Earth.”

An earth doctor is a tlamatini, wise man/wise woman (they who know things), a philosopher, teacher, practitioner of truth, and a metaphysician—a medicine person: a combination of shaman (curandero), mystic, and priest. Tlamatini are symbolized as a torch, a stout torch that does not smoke—light. They are portrayed as showing the path, the true way for others. As the true way, they are themselves black and red ink, writing and wisdom. They bestow knowledge about things difficult to understand and about the Otherworld.